Kubeapps APIs - a plugable system supporting different Kubernetes packages

The recent release of Kubeapps marks a milestone for the Kubeapps team in that we are no longer restricted to presenting a catalog of only Helm packages in our UI and, behind the scenes, we’ve addressed a long-standing security issue to remove the reverse proxy to the Kubernetes API server that our UI depended on until now. We’ve done a few overviews of the new Kubeapps APIs service which makes this possible (see Kubeapps APIs: Beyond Helm, or the TanzuTV episode 74 where Antonio gives an in-depth demo of the Carvel support), or more recently, a demo of the Flux and Carvel support together:

But in this post I’d like to write something a little more detailed about the choices we made as well as some of the implementation details.

First, there were two main issues that we aimed to solve with the Kubeapps APIs service:

1. Enable plugable support for presenting catalogs of different Kubernetes packaging formats for installation

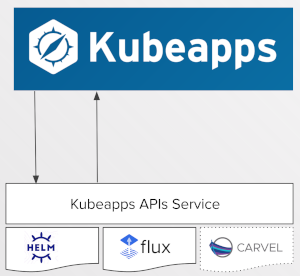

That is, we wanted to move from the situation where Kubeapps is tightly couple to the Helm packaging system:

to an API backend that can query different packaging systems in a standard way using a plugable architecture:

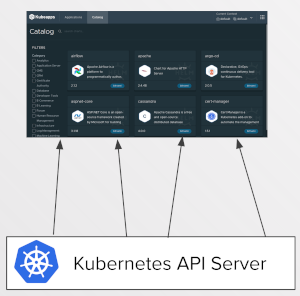

2. Remove the long-standing requirement for the Kubeapps UI to talk directly with the Kubernetes API server

That is, we wanted to move from this situation where the client code running in a browser needs to query the Kubernetes API server directly:

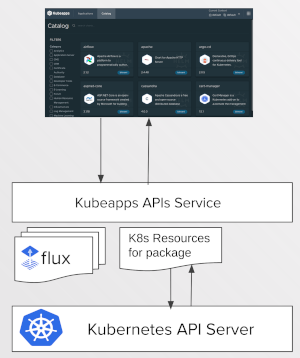

to an API backend that can be queried by the user for only the data required to use Kubeapps:

A gRPC-based API server

We chose to use gRPC/protobuf to manage our API definitions and implementations together with the buf.build tool for lint and other niceties. In that regard, it’s a pretty standard stack using:

- grpc-gateway to enable an RESTful JSON version of our API (we don’t use this in our client, but not everyone uses gRPC either, so wanted to ensure the API was accessible to others who wanted to use it)

- Improbable’s grpc-web to enable TypeScript gRPC client generation as well as translating gRPC-web requests into plain gRPC calls in the backend (rather than requiring something heavier like Envoy to do the translation),

- We multiplex on a single port to serve gRPC, gRPC-web as well as JSON HTTP requests.

What is more interesting, in my opinion, is how we used gRPC/protobuf to enable a plugable core packages interface that can be queried by the UI to return a combination of packages from different backends, such as Helm, Flux or Carvel. But before we get there, let’s briefly look at the dynamic loading of plugins as well as the authorization strategy.

Dynamic loading of plugins during startup

A plugin for the Kubeapps APIs service is just a standard Go plugin that exports a specific function with the signature:

func RegisterWithGRPCServer(

s grpc.ServiceRegistrar,

configGetter core.KubernetesConfigGetter,

clustersConfig kube.ClustersConfig,

pluginConfigPath string,

) (interface{}, error)

This allows the main kubeapps-apis service to load any plugins found in the specified plugin directories dynamically when the service starts up and call their RegisterWithGRPCServer functions. So for example, as you might expect, we have a helm/v1alpha1 plugin that provides a helm catalog and the ability to install helm packages, as well as a resources/v1alpha1 plugin which can be enabled to provide some access to Kubernetes resources, such as the resources related to an installed package (assuming the requestor has the correct RBAC) - more on that later.

Authentication/Authorization

Authentication-wise, we continue to rely on the OIDC standard so that every request that arrives at the Kubeapps APIs server must include a token to identify the user. This token is then relayed with requests to the Kubernetes API service on the users’ behalf, ensuring that all use of the Kubernetes API server is with the users’ configured RBAC. Each plugin receives a core.KubernetesConfigGetter function when being registered, which handles creating the required Kubernetes config for a given request context, so the plugin doesn’t need to care about the details.

Note that although we don’t support its use in anything other than a demo environment, a service account token can be used instead of a valid OIDC id_token to authenticate requests.

Enabling different implementations of a core packages plugin

Where things become interesting is with the requirement to support different Kubernetes packaging formats via this plugable system and present them consistently to a UI like the Kubeapps dashboard.

To achieve this, we defined a core packages API ( core.packages.v1alpha1) with an interface which any plugin can choose to implement. This interface consists of methods common to querying for and installing Kubernetes packages, such as GetAvailablePackages or CreateInstalledPackage. You can view the full protobuf definition of this interface in the packages.proto file, but as an example, the GetAvailablePackageDetail RPC is defined as:

rpc GetAvailablePackageDetail(GetAvailablePackageDetailRequest) returns (GetAvailablePackageDetailResponse) {

option (google.api.http) = {

get: "/core/packages/v1alpha1/availablepackages/plugin/{available_package_ref.plugin.name}/{available_package_ref.plugin.version}/c/{available_package_ref.context.cluster}/ns/{available_package_ref.context.namespace}/{available_package_ref.identifier}"

};

}

where the request looks like:

// GetAvailablePackageDetailRequest

//

// Request for GetAvailablePackageDetail

message GetAvailablePackageDetailRequest {

// The information required to uniquely

// identify an available package

AvailablePackageReference available_package_ref = 1;

// Optional specific version (or version reference) to request.

// By default the latest version (or latest version matching the reference)

// will be returned.

string pkg_version = 2;

}

Similar to the normal Go idiom for satisfying an interface, a Kubeapps APIs plugin satisfies the core packages interface if it implements all the methods of the core packages interface. So when the kubeapps-apis service’s plugin server has registered all plugins, it subsequently iterates the set of plugins to see which of those plugins satisfy the target core packages interface, returning a slice of packaging plugins satisfying the interface:

// GetPluginsSatisfyingInterface returns the registered plugins which satisfy a

// particular interface. Currently this is used to return the plugins that satisfy

// the core.packaging interface for the core packaging server.

func (s *pluginsServer) GetPluginsSatisfyingInterface(targetInterface reflect.Type) []PluginWithServer {

satisfiedPlugins := []PluginWithServer{}

for _, pluginSrv := range s.pluginsWithServers {

// The following check if the service implements an interface is what

// grpc-go itself does, see:

// https://github.com/grpc/grpc-go/blob/v1.38.0/server.go#L621

serverType := reflect.TypeOf(pluginSrv.Server)

if serverType.Implements(targetInterface) {

satisfiedPlugins = append(satisfiedPlugins, pluginSrv)

}

}

return satisfiedPlugins

}

Of course, all plugins register their own gRPC servers and so the RPC calls they define can be queried independently, but having a core packages interface and keeping a record of which plugins happen to satisfy the core packages interface allows us to ensure that all plugins that support a different Kubernetes package format have a standard base API for interacting with those packages (they can define other RPC functions of course), and importantly, the Kubeapps APIs services’ core packages implementation can act as a gateway for all interactions, aggregating results for queries and generally proxying to the corresponding plugin.

Aggregating results from different packaging plugins

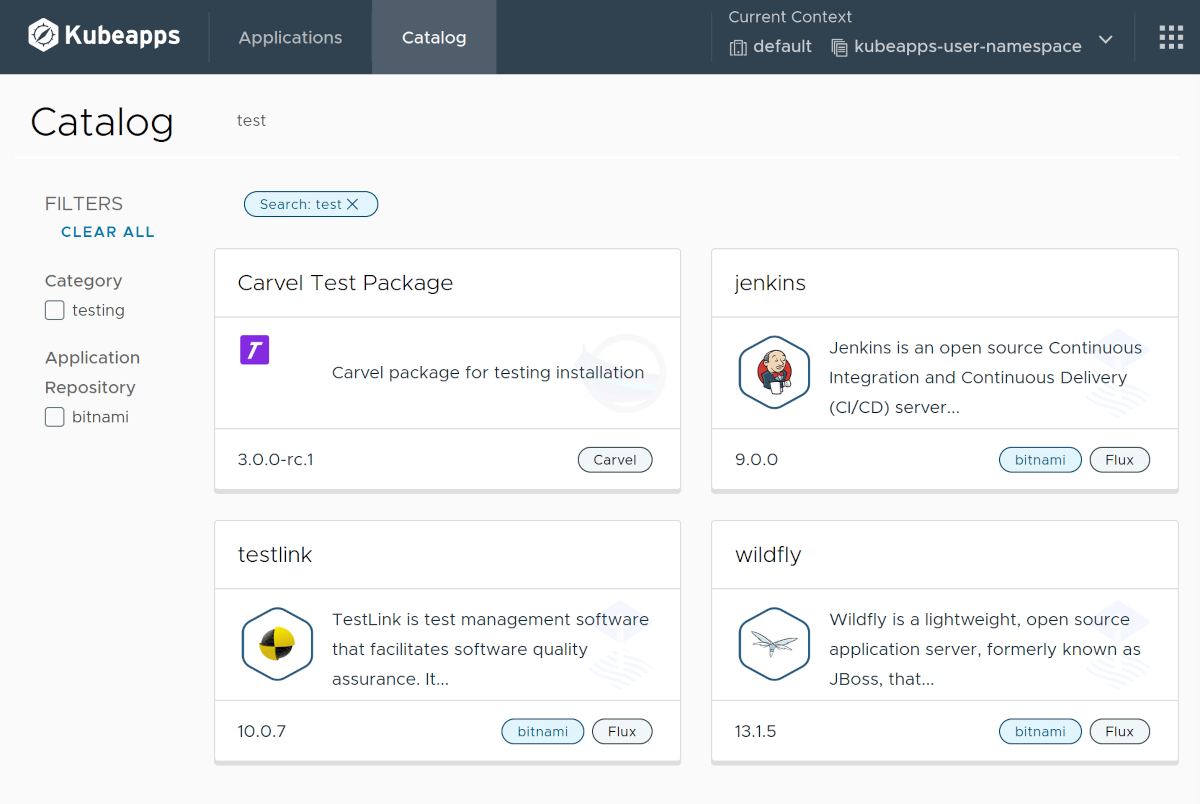

Part of the goal of enabling plugable support for different packaging systems is to ensure that a UI like the Kubeapps dashboard can use a single client to present a catalog of apps for install, regardless of whether they come from a standard Helm repository, or a flux-based Helm repository, or Carvel package resources on the cluster. With some caveats, this is what we have achieved with the latest Kubeapps release:

This is possible because the implementation of the core packages API aggregates from and delegates to the packaging-specific implementations. For example, the core packages implementation of GetAvailablePackageDetail can simply delegate to the relevant plugin:

// GetAvailablePackageDetail returns the package details based on the request.

func (s packagesServer) GetAvailablePackageDetail(ctx context.Context, request *packages.GetAvailablePackageDetailRequest) (*packages.GetAvailablePackageDetailResponse, error) {

contextMsg := fmt.Sprintf("(cluster=%q, namespace=%q)", request.GetAvailablePackageRef().GetContext().GetCluster(), request.GetAvailablePackageRef().GetContext().GetNamespace())

log.Infof("+core GetAvailablePackageDetail %s", contextMsg)

if request.GetAvailablePackageRef().GetPlugin() == nil {

return nil, status.Errorf(codes.InvalidArgument, "Unable to retrieve the plugin (missing AvailablePackageRef.Plugin)")

}

// Retrieve the plugin with server matching the requested plugin name

pluginWithServer := s.getPluginWithServer(request.AvailablePackageRef.Plugin)

if pluginWithServer == nil {

return nil, status.Errorf(codes.Internal, "Unable to get the plugin %v", request.AvailablePackageRef.Plugin)

}

// Get the response from the requested plugin

response, err := pluginWithServer.server.GetAvailablePackageDetail(ctx, request)

if err != nil {

return nil, status.Errorf(status.Convert(err).Code(), "Unable to get the available package detail for the package %q using the plugin %q: %v", request.AvailablePackageRef.Identifier, request.AvailablePackageRef.Plugin.Name, err)

}

// Validate the plugin response

if response.GetAvailablePackageDetail().GetAvailablePackageRef() == nil {

return nil, status.Errorf(codes.Internal, "Invalid available package detail response from the plugin %v: %v", pluginWithServer.plugin.Name, err)

}

// Build the response

return &packages.GetAvailablePackageDetailResponse{

AvailablePackageDetail: response.AvailablePackageDetail,

}, nil

}

Similar implementations of querying functions like GetAvailablePackageSummaries in the same file collect the relevant available package summaries from each packaging plugin and return the aggregated results. So our Kubeapps UI (or any UI using the client) can benefit from using the single core packages client to query and interact with packages from different packaging systems, such as Carvel and Flux.

It is worth noting that a plugin that satisfies the core packages interface isn’t restricted to only those methods. Similar to go interfaces, the plugin is free to implement other functionality in addition to the interface requirements. The Helm plugin uses this to include additional functionality for rolling back an installed package - something which is not necessary for Carvel or Flux. This extra functionality is available on the Helm-specific gRPC client.

Caveats

Although the current Kubeapps UI does indeed benefit from this core client and interacts with the packages from different packaging systems in a uniform way, we still have some exceptions to this. For example, Flux and Carvel require selecting a service account to be associated with the installed package. Rather than the plugin providing additional schema or field data for creating a package (something we plan to add in the future), we’ve currently included the service account field based on the plugin name.

It’s also worth noting that we tried and were unable to include any streaming gRPC calls on the core packages interface. While two separate packages can define the same interface (with the same methods, return types etc.), grpc-go generates package-specific types for streamed responses, which makes it impossible for one packages’ implementation of a streaming RPC to match another one, such as the core interface. It is not impossible to work around this, but so far we’ve used streaming responses on other non-packages plugins, such as the resources plugin for reporting on the Kubernetes resources related to an installed package.

Accessing K8s resources without exposing the Kubernetes API server

Prior to this release, the Kubeapps dashboard required access to the Kubernetes API to be able to query and display the Kubernetes resources related to an installed package, as well as other functionality such as creating secrets or simply determining whether the user is authenticated (only with the users’ credential, of course). As a result, the Kubeapps frontend service has included a reverse proxy to the Kubernetes API since the very beginning. A major goal for the new kubeapps-apis service was to remove this reverse proxying of the Kubernetes API.

This was achieved with the current release by the creation of the resources/v1alpha1 plugin, which provides a number of specific functions related to Kubernetes resources that are required by UIs such as the Kubeapps dashboard. For example, rather than being able to query (or update) resources via the Kubernetes API, the resources/v1alpha1 plugin provides a GetResources method that streams the resources (or a subset thereof) for a specific installed package only:

// GetResourcesRequest

//

// Request for GetResources that specifies the resource references to get or watch.

message GetResourcesRequest {

// InstalledPackageRef

//

// The installed package reference for which the resources are being fetched.

kubeappsapis.core.packages.v1alpha1.InstalledPackageReference installed_package_ref = 1;

// ResourceRefs

//

// The references to the resources that are to be fetched or watched.

// If empty, all resources for the installed package are returned when only

// getting the resources. It must be populated to watch resources to avoid

// watching all resources unnecessarily.

repeated kubeappsapis.core.packages.v1alpha1.ResourceRef resource_refs = 2;

// Watch

//

// When true, this will cause the stream to remain open with updated

// resources being sent as events are received from the Kubernetes API

// server.

bool watch = 3;

}

This enables a client such as the Kubeapps UI to request to watch a set of resources referenced by an installed package with a single request, with updates being returned any resources in that set changes, which is much more efficient for the browser client than a watch request per resources sent previously sent to the Kubernetes API. Of course the implementation of the resources plugin still needs to issue a separate watch request per resource to the Kubernetes API, but it’s much less of a problem than it is to do so from a web browser. Furthermore, it is much simpler to reason about with go channels since the messages from separate go channels of resource updates can be merged into a single watcher with which to send data:

// Otherwise, if requested to watch the resources, merge the watchers

// into a single resourceWatcher and stream the data as it arrives.

resourceWatcher := mergeWatchers(watchers)

for e := range resourceWatcher.ResultChan() {

sendResourceData(e.ResourceRef, e.Object, stream)

}

See the mergeWatchers function for details of how the channel results are merged, which is itself inspired by the fan-in example from the go blog.

The resources plugin doesn’t care which packaging system is used behind the scenes, all it needs to know is which packaging plugin is used so that it can verify the Kubernetes references for the installed package. In this way, the Kubeapps dashboard UI can present the Kubernetes resources for an installed package without caring which packaging system is involved.

Conclusion

The design and implementation of the Kubeapps APIs service has provided Kubeapps with a way forward to support different package formats into the future, beginning with Carvel and Flux, rather than being relevant only in a Helm-based world. We still have work to do to support custom fields in a generic way for the UI, as well as adding an API for package repositories and pagination for aggregated results, but with the Kubeapps APIs service in the current release, we have achieved our initial goals to add basic support for Carvel and Flux in addition to the existing Helm support while also removing the dependence of our browser-based Kubeapps client on a proxied connection to the Kubernetes API service. Here’s to a more inclusive and secure path forward for Kubeapps!