One of the great aspects of working at a larger company like VMware is that there are programs like Take 3, designed to help people who meet certain criteria to take 3 months on a different project to learn new skills in other contexts and bring those skills and experience back to their team - rather than potentially looking elsewhere for a similar learning experience. This post documents my own recent learning experience of an exciting Take3 project at VMware, with the hope that others may be able to take up the opportunity to learn and bring new skills back to their teams.

At the time of writing, I’ve been working at Bitnami (pre-acquisition) and then VMware for over five years, with most of that time spent improving and adding features to the excellent Kubeapps application. Kubeapps is mostly written in Go with React for the frontend, but a year or two ago when we needed a new-yet-temporary service for Kubeapps, an authentication proxy to extend the functionality of VMware Pinniped authentication project, we chose a different tool for the job. After some consideration, we designed and implemented the pinniped-proxy service for Kubeapps using the Rust language - a language I’d played with for a few years and that is widely recognised as having great potential for writing secure software into the future. Not only has our Rust-based pinniped-proxy service fulfilled its purpose ever since, but it also left me with a keen desire to continue building my skills and fluency with all aspects of the Rust - “a language empowering everyone to build reliable and efficient software”.

A learning opportunity

Right at the time that a few events at work had left me wondering whether it was a good time to look for an opportunity to do so, Leonid, a colleague from the VMware Research Group, posted about a Take3 opportunity with the Database Stream Processing (DBSP) team within the VMware Research Group. When I saw this project advertised internally, I contacted Leonid straight away as not only was it a Rust codebase but also an interesting project working with a research group that aims to put new research and ideas into the hands of users - something I’ve wanted get back to for quite some time.

Database Stream Processing - Computing over streaming data

As outlined in the DBSP Readme,

Computing over streaming data is hard. Streaming computations operate over changing inputs and must continuously update their outputs as new inputs arrive. They must do so in real time, processing new data and producing outputs with a bounded delay.

A simple, relevant example of streaming input is a stream of events comprised of new users, new auctions and new bids on those auctions. The output of the computation might (rarely) be as simple as the same streamed data in a different currency, or a more complicated computation such as a stream of the average selling price for each seller, for their last 10 closed auctions. Given that the input stream can be infinite, the computation must be bounded in some way: calculating the average selling price for all sellers for all their auctions through time leads to an infinite storage requirement, so the data is chunked into smaller windows of data (you can read more about windows of streamed data in the Apache Flink documenation.

One major difference that the DBSP project offers is the ability to maintain both the output stream and the intermediate states via incremental updates, operating only on changes of the data. For example, rather than maintaining the average selling price for each seller by re-evaluating the set of last 10 closed auctions for each seller as more data arrives, a DBSP operator can add or remove closed auctions from the intermediate calculation only as they change, which in turn enables another chained DBSP operator to output events only when the aggregate changes. Although the example is not perfect (this query can also be done efficiently with existing stream processing applications), the intent is to outline how DBSP’s incremental operators provide an expressive language for complex queries of streamed data to run more efficiently than would otherwise be possible. Where existing data processing systems require batch mode to execute more complex business logic queries, DBSP promises to do so as a streaming computation.

Benchmarking DBSP

The goal of my work with the DBSP project was to investigate and implement the Nexmark Benchmark for streaming computations using DBSP, which would also help identify as-yet unimplemented functionality in DBSP. Specifically, my work during the 3 months of the Take3 opportunity can be broken down into roughly four components, which I’ll detail separately below:

- writing a Rust version of the Nexmark event generator,

- writing the Nexmark queries using DBSP operators,

- writing the benchmark binary, and

- reproducing the original Nexmark benchmark results and the DBSP results on the same (virtual) hardware.

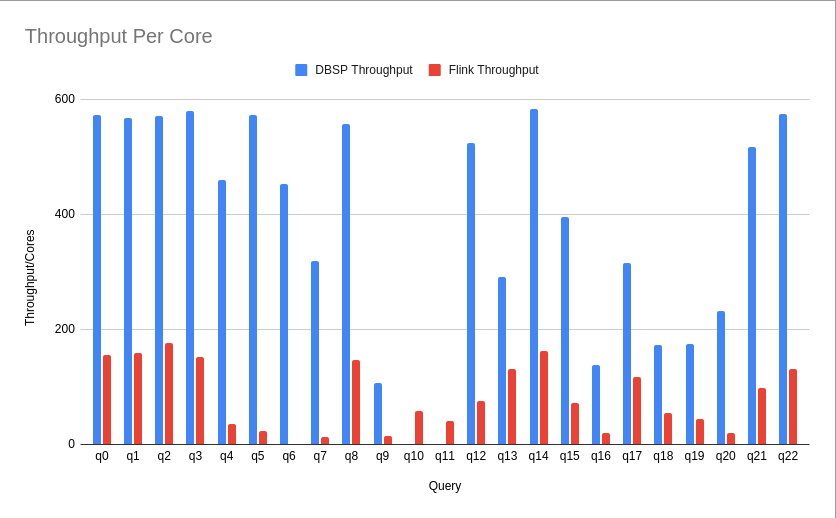

The preliminary result was that we could show that DBSP can run the Nexmark Benchmark queries on average nearly 4 times faster with 7 times the throughput per CPU (ie. less CPU cores), using a single machine with 16 cores, rather than a cluster of machines (with 16 cores each, though the Java/Flink benchmark does not utilize all 16).

1. A Rust Nexmark Event Generator

Initially I spent some time investigating whether we could re-use the Java Nexmark source generator, but found it to be a specific implementation of the Nexmark data source for running against Flink. That is, although the code includes a generic nextEvent implementation that generates a bid, auction or person in the correct proportions, it integrates this generator with Flink-specific Java functions and extends Flink’s RichParallelSourceFunction class to provide this generated data specifically to Flink. I spent some time looking for ways that we may be able to use this as an input (including the interesting JAVA for Rust crate), before looking for any similar Rust implementations. In the same way, the only existing Rust implementation of the Nexmark Source that I could find was specific to the project being benchmarked (in that case, Megaphone).

So I began porting the Java implementation to create a generic Rust Nexmark source event generator, with the intention that we could move it to a separate repository and use a gRPC interface or similar so that it’s a language-independent Nexmark source. It wasn’t a straight port, nor was it always easy to understand the original intention for different parts of the codebase, and sometimes I found what appear to be small issues, but for the most part it was great to apply and extend my existing Rust skills on a known specification, with very helpful reviews from Leonid and Chase usually resulting in simpler code due to Rust’s language features and macros.

As a simple example, the Java implementation for a Nexmark Event is a class with 3 nullable fields for a possible Person, Auction or Bid, together with a Type enum that specifies which type of event is represented by the object. It then also overrides equals, hashCode and toString with specific implementations. Compare that with the equivalent Rust implementation which does all of the above in 6 lines by using macros to automatically derive the Eq, Hash, and Debug traits, and uses a Rust Enum with an associated data rather than a full-blown struct/object:

|

|

With a single thread generating the Nexmark events, I could process 1.5M events per second with the q0 no-op query, which, interestingly, matched the throughput/elapsed time of the Java implementation (~70s for 100M events):

|

|

but was clearly bound by the generator thread, with 43.7% of the processing time spent generating the next event, as can be seen by the flamegraph generated with:

|

|

(Open the flamegraph in a new tab for a larger, interactive flamegraph)

Clearly the Nexmark Source would need to be multi-threaded to generate events at a sufficient rate, but the events must also be generated in the specified order. I’d recently written about using buffered Go channels with the Fan-out/Fan-In pattern, and it turns out that we can do the same pattern using Rust’s standard mpsc channels so that a configurable number of generators run, each in their own thread, as shown in the following code which returns a vector of read handles to the buffered channel for each thread, as a good example of Rust’s functional language features:

|

|

The map of lines 3-10 creates a generator config with the first event number configured to the generator number. Lines 11-26 then map each generator config to spawn a new thread with that config that simply calls next_event() and sends the next event down the channel for that thread. So generator 0 will begin with event 0 followed by event N, 2N, 3N etc., while generator 1 with begin with event 1 followed by 1 + N, 1 + 2N, and so on until each buffer is full. All the Nexmark source then needs to do is start another thread which reads from each channel in a round-robin pattern to send the events in order down the single output channel for the consumer. With this pattern, we can get the elapsed time for processing 100M events down to 18s, with a throughput of 703K events per second on each core.

|

|

Checking the flamegraph of the same, we see that together the 8 generators are using a similar amount of CPU time (40-45%) as before, but distributed across the 8 threads means that the elapsed time to generate the events is around 1/8th of what it was previously, while other code that previous waited on the source for the next event no longer waits as long.

The chart below charts the rate at which events are processed for q0 with a growing number of generators, peaking at around 7 or 8 generators:

Of course, the Nexmark source is unit-tested as is the generator code, to ensure that the correct events are generated in the expected order. Note that, similar to the original Java implementation, the Nexmark source never floods the process with extra events, but rather, new events are only generated when there is space in each generator’s buffered channel. If you’ve not used the Fan-out/Fan-In pattern mentioned above, I’d encourage you to read Fan-out/Fan-In pattern with Go-lang and Kubeapps or watch the 3D demo with the excellent Infinifactory game

:2. Writing the Nexmark queries using DBSP operators

While working on the above Nexmark source generator, I also began learning more about DBSP’s operators and how to use them to replicate similar SQL functionality to write the 22 queries that comprise the complete Nexmark benchmark suite. The task began with simple inner joints and worked towards more complicated queries.

A simple example: Nexmark Query 3

As an example, the 3rd Nexmark query filters to find seller and auction details for auctions in a certain category sold by sellers living in selected states. So the SQL looks quite straight forward as it is identical to a non-streamed SQL query:

|

|

The equivalent DBSP query is a little more verbose without its own domain-specific language, but benefits from the full expressiveness of Rust’s functional features:

|

|

The flat_map_index DBSP stream function takes a closure that receives an event and returns either a 2-tuple of the index value and related values, or None, with the resulting stream emitting the indexed values. So line 3 above creates a stream auction_by_seller of auction ids indexed by the seller id, for only those auctions of the specific category. Similarly, line 9 creates a stream person_by_id, of people’s data for those people who live in the specific states. Finally, line 18 performs a join on the two indexed streams, joining on the person id to return the name, city, state and auction id for all people who created an auction with the specified category who also live in one of the specified states.

Where the Flink cluster of 8 machines takes 76.5s to process 100M events, the DBSP query in rust, running on a single machine but utilizing 8 cores, takes 21.5s.

A more complicated example: Nexmark Query 5

Let’s look at a more complicated query that benefits from DBSP’s expressiveness. Below is the Flink SQL query for Nexmark query 5. It is hard to decipher, but the aim is to show the auctions that have had the highest number of bids in the last 10 second window, with a new window created every 2 seconds (ie. if the first window is from 0-10 seconds, the next is from 2-12, then 4-14 etc.):

|

|

The equivalent DBSP code for q5 is both shorter (with comments removed) and more expressive - though still complicated due to the nature of the query. Let’s take a look step-by-step.

First, we need to define the 10 second window as the query progresses, so we start by creating a stream of auction ids for bids, indexed by the time of the bid:

|

|

When doing calculations and aggregates on streaming data, one important point is that data can arrive both late and hence, out of order. For this reason, we don’t want to calculate our 10 second window up until the current time, but rather, define a watermark, an interval into the past, at which point we consider all data to have arrived, allowing a consistent calculation. In our case, we have a constant WATERMARK_INTERVAL_SECONDS set to 4 seconds to match the Flink configuration, which we use to define the watermark stream function for any given date time, as 4 seconds in the past:

|

|

which we then use to create the window bounds: for each date_time of the watermark, we first floor the number to the nearest two seconds (TUMBLE_SECONDS is set to 2) and use that as the upper bound of the window, with the lower bound being 10 seconds earlier (WINDOW_WIDTH_SECONDS is set to 10):

|

|

Now we can use our window bounds to limit the indexed bids to those present in the window, giving us a stream of auction_id’s from the bids in the defined window only (it’s not obvious, but the window function consumes the date_time):

|

|

Next, we aggregate the auctions - simply counting 1 for each so we have, for each auction_id, how many bids were made during the defined window, then pass this stream into another aggregate, this time creating a stream of the maximum count of bids for the window:

|

|

then use the maximum count as an index to join and single out the matching auction id with the maximum count (though there may be more than one with the same maximum - see the test_q5::case_3_multiple_auctions_have_same_hotness below):

|

|

This query, Nexmark query 5, takes 418s to process 100M events on the Flink cluster of 8 machines, whereas DBSP is able to process the 100M on a single machine utilizing 8 cores in 22s, almost keeping up with the input. Note that there is a small difference in the expectations of the query definition, in that, theoretically, Flink is calculating all 10 second windows concurrently, but with the Flink configuration used (in particular, the 4s watermark) previous windows are not changing.

Testing to ensure the query results

That’s all well and good, but we need to be sure that the query is in fact giving the expected result. For this reason, each DBSP rust query has unit tests to verify that, given certain input bids at different times, the expected output matches the actual output. For details, see the query 5 test cases in the project repository. Each test can be run via cargo test:

|

|

Most of the queries were somewhere in between the above two examples in complexity, though some required new DBSP features which Leonid added as we went. You can see the full list of 20 queries (with their tests) in the repository. We skipped one query which was related to logging only (q10) and postponed implementing one other which depends on session windows (q11), for which the DBSP project does not yet have equivalent functionality.

3. Creating the Benchmark binary

Once the initial Nexmark Source event generator and the first few queries were created, I was able to setup the actual benchmark binary. This turned out to be a good opportunity to work with Rust’s procedural macros, as well as learn more about measuring resource usage on linux and interfacing with the C standard library. The end result is a UX using Rust’s cargo tooling to run benchmarks, such as the following for running the Nexmark query 5 for 10M events:

Rust’s procedural macros

As soon as I was benchmarking more than one query, I hit the problem that each query function has a different type, since the output stream differs. As a result, I could not create a DBSP circuit able to take arbitrary Nexmark queries, but I could define a procedural macro that produces code for a circuit of arbitrary output type:

|

|

The above macro takes a single argument as an argument, $query, which is substituted into the code matching that pattern, defining the DBSP circuit and returning the input handle. But even with this macro, one query in particular, q13 had not only a different output stream type, but also a different number of inputs to use. Luckily, for Rust’s declarative macros, it’s simply a case of defining a different pattern with the query already specified to generate the alternate circuit:

|

|

Measuring memory and CPU usage

Up until the last few weeks, I was using the C standard library getrusage call to measure the CPU and memory usage of queries. Though this had certain limitations, it enabled statistics for the CPU usage (user and system) as well as memory usage (Max RSS) for one query at a time. Interfacing with the C standard library was also an learning opportunity, as was creating some unsafe Rust code for the benchmark to use. Chase later updated the memory allocator used in DBSP (and hence the Nexmark benchmark binary) to use Microsoft’s mimalloc, which is more performant than the default Rust memory allocator, and updated the calls to getrusage to instead use mimalloc’s own statistics support.

4. Automating the environments for testing the original Flink Nexmark benchmark results and the DBSP results on the same (virtual) hardware

We managed to complete the Nexmark benchmark functionality and associated changes to DBSP with around one week left of my Take3 adventure. So Leonid’s suggestion was to see if we could setup a Flink cluster to run the original Java Nexmark benchmark suite and then run the DBSP benchmark on one of those machines, so the comparison would be running on the same hardware (even though DBSP requires only one machine).

I didn’t want to do the setup ad-hoc and not be able to have someone else reproduce the results easily, so decided to do this using Ansible to configure the machines so the Flink benchmark can be run with a few simple commands. The end result is the Nexmark Flink DBSP Configuration repository which can be used to do all the installation and configuration required for running both the Flink and DBSP benchmarks.

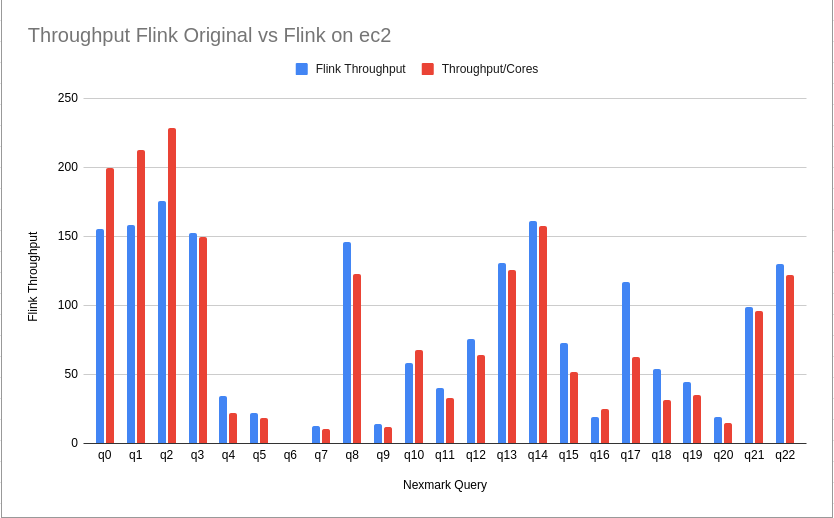

As outlined in the repository’s Readme section for the Flink result, I was able to reproduce the throughput of the original results for each query with the configured Flink cluster of 8 worker instances and one leader:

but I could not resolve an issue where I would see queries completed in terms of the data processed and CPU usage (which I could watch via htop on workers) while the Flink leader did not acknowledge them as complete until some seconds later, which exaggerated the elapsed time on my Flink cluster.

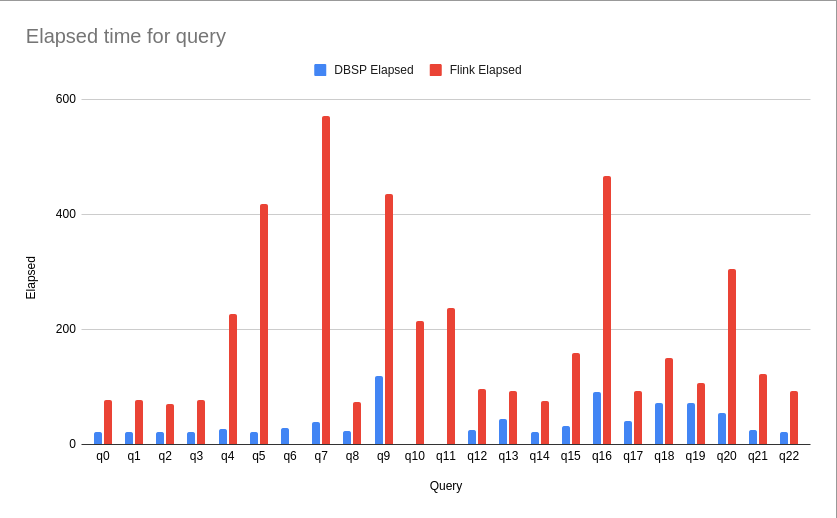

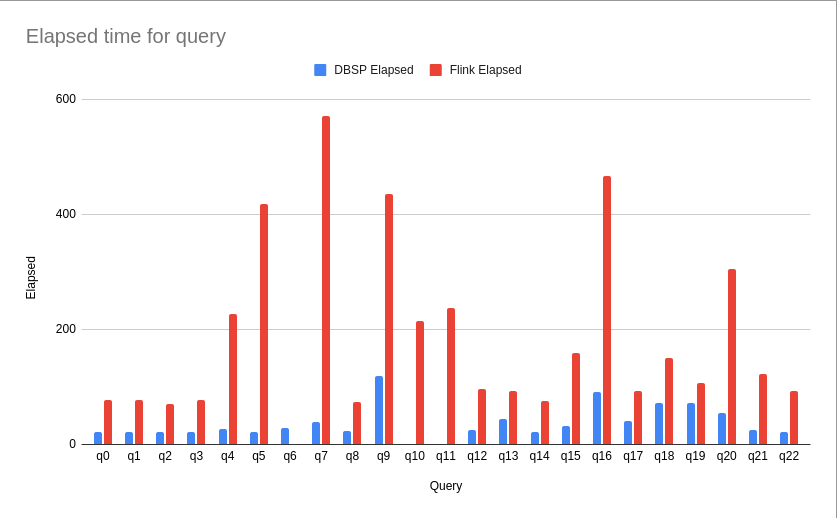

Nonetheless, having a similar throughput to the original results enabled me to then run the DBSP benchmark on a single instance of the same type (an ec2 m5ad.4xlarge instance which has 64Gb RAM, 16vCPU, and 2x300GB SSD), comparing both the elapsed time for each query as well as the throughput per core:

Conclusion

All in all, thanks to the support from Leonid and the DBSP team, as well as my own manager Pepe, the Take3 has been a wonderful learning experience that has helped me refine and build my existing Rust skills and fluency as well as meaningfully contribute to a current research project. As it turns out, the original functionality for which we created the pinniped-proxy in Kubeapps with Rust - the ability to authenticate users of web applications - has recently been added to the VMware Pinniped service. So one of my first tasks back on the Kubeapps team may be to update our proxy to use the new authentication functionality.